“Dandyism, which is an institution outside the law, has strict laws to which all its subjects are rigorously bound, regardless of the ardor and independence of their character.”1

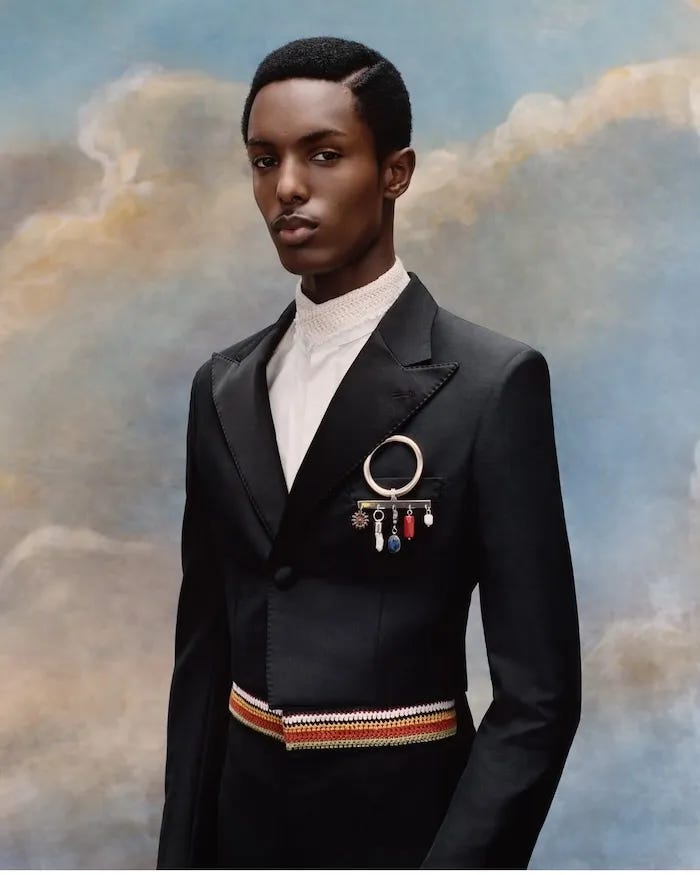

The dandy is not an ordinary person; his goal is to shock the observer rather than to please others, and he is in constant pursuit of an abstract ideal. This ideal has endured for more than two centuries and remains today the ultimate symbol of refinement and elegance in defiance of the status quo.

The dandy has held a significant place in society and has influenced history, with each generation creating its own version marked by distinctive characteristics. From an act of insurrection in the 19th century, to breaking gender boundaries in the 20th century, to serving as a foundational concept in the making of media celebrities, dandyism remains today a mirror of society and its era. In their constant search for new behaviors, dandies have often tested the limits of eccentricity, always while displaying a recognizable mark of elegance—a source of inspiration for today’s fashion trends.

As a phenomenon focused on impression, dandyism uses details as media tools, transforming the dandy’s “unique personality” into a recognizable figure. Labeled as non-conformist, it is through the effect of the collective that the figure of the dandy is revealed. This is a non-conformity in perpetual tension, playing with political correctness while maintaining elegance and restraint. It is through this ongoing tension with the group that the dandy constructs himself, like an “aristocrat of the soul” as Baudelaire wrote, preferring nobility of spirit over social status.

The dandy's individualism is reflected in a gaze turned inward, to the point of aestheticizing the world through his own person.

“The ultimate goal of a dandy is to be recognized—recognized as a living object or, failing that, as a visual object. The dandy’s play with old forms allows only a limited number of combinations; appearances are never destroyed, but simply recombined and given a different meaning.”2

By considering the many figures and portraits of dandyism, the term ultimately comes to represent more of a mythical figure, transcending its original historical framework. Characters such as Lord Seymour, Marcel Proust, or Oscar Wilde, for example, do not entirely conform to the myth of the dandy but each represent, in their own way, a certain manifestation of it.

According to Roland Barthes, the creation of “myths” in our modern society is the product of the contemporary system of social values. Dandies, as “myth-makers”, gather signs, codes, and symbols—along with their connotations—in order to communicate a social and political message. The dress codes accepted by society as a whole can be redefined or even erased to give rise to a new system of meaning.

By setting themselves apart from social norms and traditional gender roles through their clothing choices, dandies challenge conventional ideas of what is considered acceptable or desirable: “the dandy rejects dogmas and injunctions, opposing the singular to the multiple, the little to the excessive, leisure to labor, gratuity to profit, wealth to enrichment, reserve to outpouring, and the delirium of his rigor to the dreary economy of households.”3 This spirit of individuality and non-conformity has continued to influence contemporary countercultural movements and remains a relevant aspect of dandyism today.

“The original singularity of the dandy does not rest on a notion of truth but on a strategy of social legitimization. The dandy becomes an individual only once others grant him that status. He distinguishes himself by the way he directs his gaze and draws the gaze of others onto himself.”4 The dandy is created and exists only through the gaze of others, and recognition of his persona is almost proportional to his absence—his notoriety tends to increase as he fades from view.

It is also interesting to note that at the dawn of the first dandies, only caricatures allow us to attest to their appearance, since no paintings were made of these figures. Caricature thus becomes a part of dandyism, being “the only way to depict these fashions, since dandyism itself is a caricature of fashion.” The dandy presents himself as an enigma, projecting a mysterious, unfinished character and therefore one in constant evolution. Dandyism is a “reverse labor,” it “seeks a past, ancestors, though it has no heirs.”

Could it be, then, that fashion is the terrain where the dandy asserts his identity? According to Barthes, fashion allows us to “tame the unexpected without removing its unexpectedness,”5 and the dandy’s excesses are grounded in convention, which rules out the possibility of total transgression. The dandy thus affirms his identity through this self-fragmentation, like a chameleon, and appropriates the very essence of fashion—being a caricature of oneself, a form of self-celebration.

“Unlike his contemporaries, Brummell rejected the fashions of his time—he refused the bright colors of embroidered fabrics and diverted attention away from the extravagant ornaments found on waistcoats, shoes, etc. Instead, he focused on the body and used clothing to draw attention to and enhance the human structure.”

Embodied through small differences, he can identify with all classes and social statuses, thereby maintaining a bold fluidity.

Le Peintre de la Vie Moderne, Charles Baudelaire, Le Figaro, 1863.

Fashion, Desire and Anxiety: image and morality in the twentieth century, Rebecca Arnold, Bloomsburry Publishing, 2001.

Dandies, Baudelaire&Cie, Roger Kempf, Édition Points,1977.

Le dandysme et la crise de l’identité masculine à la fin du 19ème siècle : Huysmans, Pater, Dossi, David Tacium, Université de Montréal, 1998.

Le dandysme et la mode, Œuvres complètes II, Roland Barthes, Éditions Seuil, 1962.