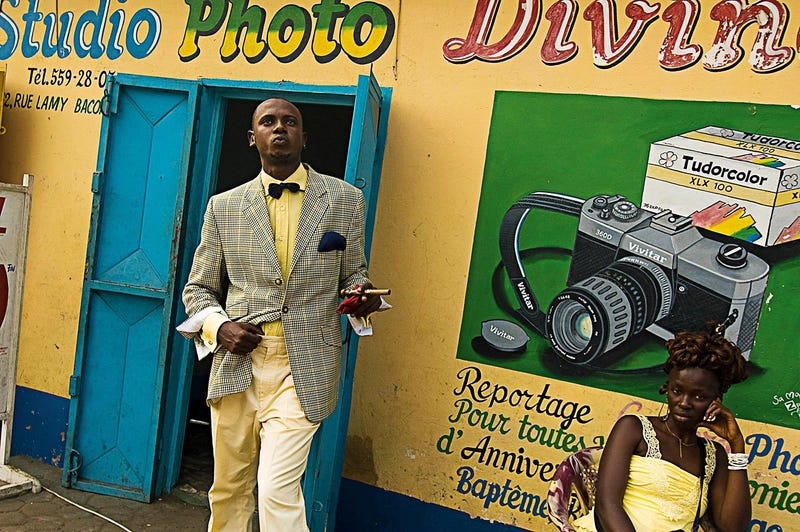

Always attentive to detail, the patterns and techniques used in this collection mimic illusions and trompe-l'œil effects, reappropriating the ordinary to elevate it. This approach can be linked to the movement of the Congolese Sapeurs, who, through the Société de la Sape (The Society of Ambiance Makers and Elegant People), imitate the classic French "dandy" style with a defining twist in their choice of colors, cuts, and accessories. The term also derives from the French slang "se saper".

This subculture, which emerged in the early 20th century under French colonial rule in Congo, draws its sartorial inspirations from the jazz movement of the 1920s and the refined fashion trends of that era. The first parades and competitions began in the neighborhoods of the two Congolese capitals, Brazzaville and Kinshasa. Following the same rules as dance battles, Sapeurs showcase, perform, and prove their skills and abilities, their gestures and voice, their walk and gaze. More than just wearing dazzling clothes, verbal and visual communication is essential to standing out.

“Throughout both cities, crowds became trained to watch these stylish duels, cheering for these "Black aesthetes"—living works of art, dressed even more elegantly than the colonial authorities themselves.”1

The Sapeurs operate within the movement of "Black dandyism," where dandy style is not just about form or substance but also, and most importantly, about intellectual and sociological liberation from rigid limitations. The dandy reclaims the classic fashion codes of European style—those of their colonizers—infusing them with an aesthetic and sensibility unique to the African diaspora. This parallel creates a rupture between the oppressed and the oppressors, challenging the stereotype of the modern Black man.

By reclaiming the characteristic fashion of their colonizers, the Sapeurs construct a new postcolonial identity, altering the discourse of power. The sartorial codes of La Sape illustrate the concept of being "almost the same, but not quite," in relation to European luxury menswear. These same European sartorial codes are used by the Sapeurs as a tool of emancipation—an "ecstatic celebration of equality through the symbolism of clothing." As a new generation of Congolese came to Paris to study, the movement cross the country to establish the MEC (Maison des Etudiants Congolais) in the 3rd arrondissement of the French capital.

“The MEC is the Mecca of the Sapeurs. Pretty much everything started there. It was a party all the time competitive moments but in good spirits and in the Sape. You could see the silhouettes all dressed up. The colours and brands were all singing. It was a sight to behold. At the MEC, the rule was to be well dressed, to shout it, enjoy it and even swear by it.”

In both of these cases, past norms are embodied by a dominant capitalist and institutional system. "

This revised version of the dandy protests against modern industrial capitalism, which has become the foundation of contemporary studies on the stereotype of the homosexual man, as well as the basis for a theory promoting queer 'style'." 2

Meet Paris’ Black Dandies, the Sapeurs, the Conversation, 2024

The Philosophy of Dandyism, Fear Christopher