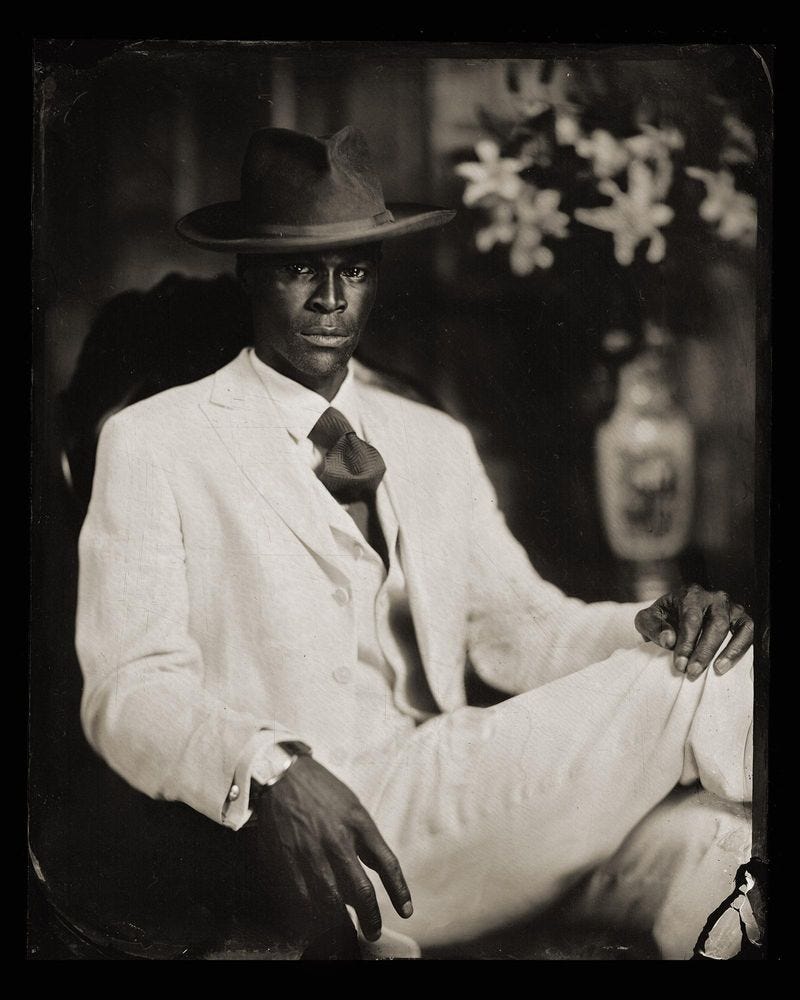

Today, the term is commonly used to describe a fashion style that incorporates classic tailoring, vintage references (usually from the early 20th century), and a measured use of flamboyance (often bold colors and patterns, sometimes formal yet always ostentatious). The dandy paradoxically celebrates the virtue of nonchalance while engaging in discussions about sartorial rules. Concepts of traditional craftsmanship, sophistication, and nostalgia have blended into the modern use of the term "dandy". As such, dandyism can be seen as the embodiment of contemporary nonconformity, emphasizing individuality and a rejection of the status quo—values often associated with rebellious attitudes. By deviating from social and traditional gender norms through their sartorial choices, dandies challenge conventional ideas of what is considered acceptable or desirable.

“The dandy rejects dogmas and injunctions, opposing the singular to the multiple, the minimal to the excessive, leisure to labor, gratuity to profit, wealth to enrichment, reserve to effusion, and the delirium of his rigor to the dull economy of households.”1

This spirit of individuality and nonconformity has continued to influence contemporary countercultural movements and remains a relevant aspect of modern dandyism. Monica Miller, professor of African Studies at Barnard College in New York and author of Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, summarizes this nonconformity as "a figure of tension", stating: "It is a tension between being Black and White in my work, a tension between heterosexual/homosexual, feminine/masculine, upper-class/lower-class individual."2

In the “The Suit: Form, Function and Style”, Chris Breward, director of the National Museum of Scotland, takes this idea even further, attributing a revolutionary character to the dandy: “The dandy could reclaim his place as a revolutionary figure who challenges our preconceived notions of what it means to be fashionable, elegant, stylish, masculine, feminine, or binary.”3

In reality, the dandy would pay little attention to the deeper value of clothing itself. Baudelaire touches on this question of attire very briefly, with a detachment that is itself imbued with dandyism: "Dandyism is not even, as many unreflective people seem to believe, an excessive taste for fashion and material elegance. Only the overall impression matters."

"Clothing has nothing to do with it. It almost ceases to exist." 4

It is precisely through this process of emphasizing the human structure—embracing a framework that goes beyond mere clothing as commercial products—that the dandy achieves self-realization.

Dandies, Baudelaire&Cie, RogerKempf, ÉditionPoints, 1977.

Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, Monica L. Miller, Duke University Press, 2009.

The Suit: Form, Function and Style, Chris Breward, Reaktion Books, 2016.

Du Dandysme et de George Brummell, Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly, B. Mancel éditeur, 1845.