the Dandy Woman - part 2

or how the codes of dandyism reinvented a gender-neutral wardrobe

“Her hands are gloved, she is helmeted, and inaccessible; a cold and disturbing beauty [through which] pierces a formidable being — this woman is free!”

The female dandy, although profoundly different in her motivations and demands from her male counterpart, shares common political and societal foundations with other figures of the movement. Her approach can notably be compared to that of the Black dandy, whose origin is also rooted in an appearance that aims to be equal to, or even superior to, the domination of the White man. Much like the Black dandy reclaims colonial markers of superiority (Western elegance, tailored suits) to challenge white supremacy, the female dandy reclaims patriarchal symbols of authority to assert feminine or non-binary sovereignty.

“Masculine-of-center women... face just as much if not more harassment by police as cis-gender men. This harassment is oftentimes linked with dress codes and for some women, dandyism is a reaction to that level of gender violence.”

-The Dandy Lion Project

Symbolizing an elegant rejection of utilitarian values, the dandy cultivated aesthetic refinement, irony, and detachment. Traditionally male-coded, women, too, appropriated this identity—transforming it, politicizing it, and redefining its boundaries. The female dandy or quaintrelle, far from being a mere imitation, embodies a bold reconfiguration of femininity and style as a form of resistance. The female dandy often chose tailored suits, ties, short hair, and neutral or monochrome colors—reconfiguring elegance not as a sign of femininity but as a form of power and authorship over one's own image. She often choses tailored suits, ties, short hair, and neutral or monochrome colors—reconfiguring elegance not as a sign of femininity but as a form of power and authorship over her own image. From object to subject, the female dandy transforms the gaze. She is no longer a passive object of desire, she becomes an active subject—controlling how she is seen and what her appearance communicates.

And as her masculine counterpart, the quaintrelle uses clothing as her first primary form of weapon. Where male attire signified authority, rationality, and respectability, women like George Sand and Marlene Dietrich wore men’s clothing not for fashion but rather for the symbolic access to those traits.

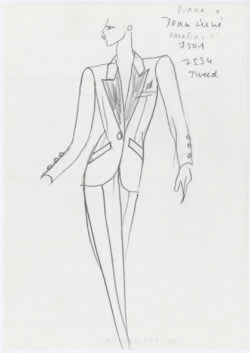

In the Fall-Winter 1966 collection, Yves Saint Laurent introduced the most iconic piece of his style: the tuxedo. Originally, a men's garment exclusively for the smoking room (from which it gets its name) as the jacket worn there served to protect clothing from the smell of cigars. Due to its use, the garment was exclusively masculine at the time.

However, the Saint Laurent tuxedo is not merely a copy of a men's piece. Yves Saint Laurent used its codes while adapting them to the female body.

“For a woman, the tuxedo is an essential garment in which she will always feel fashionable because it is a matter of style, not fashion. Fashion fades, but style is eternal.”

- Yves Saint Laurent

By dressing “like a man,” the female dandy exposes how gender is a performance—an idea later developed in feminist theory by Judith Butler: her look says: “femininity is not natural—it’s constructed.”

As a political embodiement, the female dandy became a symbolic expression for the queer community. The female dandy often embodies more than just a challenge to gender roles—she challenges heteronormative sexual expectations. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many women who embraced the dandy aesthetic were lesbians, bisexuals, or engaged in non-heteronormative sexual practices. Figures like Natalie Clifford Barney, a writer and socialite known for her lesbian relationships, or Romaine Brooks, a portrait artist and lover of women, used their style to assert queer identities that were both public and unapologetic. Their dandyism was not just about fashion, but a declaration of sexual and romantic autonomy outside the confines of traditional heterosexual norms. Queerness in dandyism goes beyond simple gender performance—it encapsulates an entire rethinking of sexual and romantic identity. The androgynous or gender-neutral female dandy does not fit into traditional heterosexual frameworks of womanhood or sexuality. This non-conformity allows the dandy to exist as a queer space, fluid in both gender and sexual orientation. opening up a space for non-binary identities. The female dandy’s queerness goes beyond mere aesthetic rebellion: it serves as a challenge to the very foundations of gender and sexual norms.

“The dandy is neither traditionally feminine nor masculine. Rather, the dandy is an aestheticized androgyny available to men, women, and transgender individuals. Herein lies its power and its danger.”

-Sophia Wallace, visual artist

The intersection of queer identities with race, class, and ethnicity has led to new forms of queer dandyism, especially in communities of color. The Black dandy movement can be traced to figures such as Josephine Baker, whom combined the cultural influence of Blackness with the defiance of mainstream, white, bourgeois aesthetic codes. The Black female dandy, in particular, reclaims both the representation of Black womanhood and the traditionally white-dominated narrative of dandyism.

Through fashion, performance, and visibility, the female dandy embodies a fluid, non-binary approach to gender that is fundamentally feminist and queer. She refuses to be confined by the limitations of femininity, embracing instead a world where gender and sexuality are both self-constructed and self-determined. The queer female dandy’s legacy offers a powerful model for subverting oppressive structures, creating space for sexual autonomy, and redefining beauty on her own terms.